We were recently asked to provide evidence for claims made in an interview with ITV Tonight, at the request of their legal team. Which is one way to spend your Saturday…but also had me thinking about the official government statistics relating to adoption in England and Wales, and the fact that as adoptees we are almost completely absent from the records. Because there are no official statistics about what happens to us after adoption, we have to rely on research studies. And because there are so few research studies on adult adoptees, we are left to rely on anecdotal evidence such as the observations made by Paul Sunderland. But why are we so invisible in official statistics?

It’s not that there is no information about adoptions. Since 1927 when the first adoption orders were issued, the following information has been collected:

- number of adoption orders made and numbers of children adopted, by year

- number of entries made in the Adopted Children Register, by year

These numbers are further broken down, at various times since 1927, by

- sex and age of the child at the time of adoption

- which court issued the adoption order (High Court, County Court, Juvenile Court)

- whether the adopted child was ‘legitimate’ or ‘illegitimate’ (later referred to as born within marriage or outside marriage)

- whether the child was adopted by their mother, father, or both, or another relative, or by non-relative(s) (later changed to parent or non-parent; later still: step parent or not step parent)

- whether the child was adopted by a couple, a single man or a single woman

- whether the adoption was contested or not (in other words, was it forced—so much for forced adoptions being ‘historical’)

However, there is almost nothing about what happens after the adoption order is issued. Our status as adoptees is not always known to schools, doctors, or other professionals unless parents, or adults who know they are adopted, choose to disclose. There is no flag or monitoring, even in mental health services where this information can be critical to our care. We disappear into the general population and there is no information about our health or educational outcomes, mortality, diseases, mental health, marriage and divorce, rates of homelessness or incarceration, and so on. For a nation historically obsessed with granular statistics about births, marriages and deaths including infant mortality, prevalence of disease, causes of death and so on, we are extraordinarily blasé about the outcomes of adoptees.

Even adoption agencies themselves are not mandated to seek or hold information about what happens to people after they are adopted. In the 2010s the Department for Education was being asked for information about rates of so-called adoption disruptions or breakdowns—where an adoptive parent asks for their child to be taken back into care. The government had no statistics and so had to commission and pay for a research study by academics, to gather and interpret data.1 They, in turn, relied on surveys sent out to social services departments and voluntary adoption agencies. Not all of them replied and not all of them had the information requested. So the result of the study was a best estimate, and we still do not know the true rate of adoption breakdowns. Ofsted reported on adoption disruptions but only those which take place prior to a child’s final adoption order.2 Again, adoptees are absent.

Some of this is due to the secrecy built into adoption, which has a history of its own and is long overdue for reform (astonishingly, there is to this day no requirement to tell your adopted child they are adopted). But mostly it is a lack of regard. No one wants to hear from the actual people affected, or cares to ask us about our experiences. In 2022, the professional body representing voluntary adoption agencies commissioned an ‘independent’ report to ‘articulate the value of adoption.’3 Did they look at actual data about adoptees through different stages of our lives? No, because there isn’t any. Instead, they made wild lifelong projections based on the differences in outcomes between children and young adults in the care system and those who had been adopted. Yet adult adoptees exist—or do we? Sometimes it feels as though we are invisible. The conclusions of this ‘independent’ study were taken as fact by the Public Law Working Group, and cited in their report although not directly relevant to their inquiry.4

Somewhat more substantive is a CoramBAAF literature review commissioned by Adoption England and published in 2023. This found a very small number of studies on outcomes of adult adoptees, and was more concerned with comparing adoptees to those raised in the care system than in comparing adoptees to those raised with their natal families (kept people).5

One result of this lack of reliable information is that when we speak about our individual stories we are met with a dismissive “I’m sorry you had a bad experience” (implying that it’s not representative). We would dearly love to have reliable information and to not speculate, generalise or argue by anecdote. We would love to have something better than a decades-old US study to quote about the high rates of attempted suicides among adoptees, but we don’t, so we will continue to cite that study.6

Another is that we are perpetually locked in childhood, infantilised and with no agency. It’s as though the public perception of adoption is a fantasy about infants and children, and they only want to hear from older adult adoptees if we are exposing ourselves to bring a tear-jerking reunion story to their screens. Even then, we must speak in thought-stopping cliché and tiptoe around the needs and feelings of the real adults, our parents.

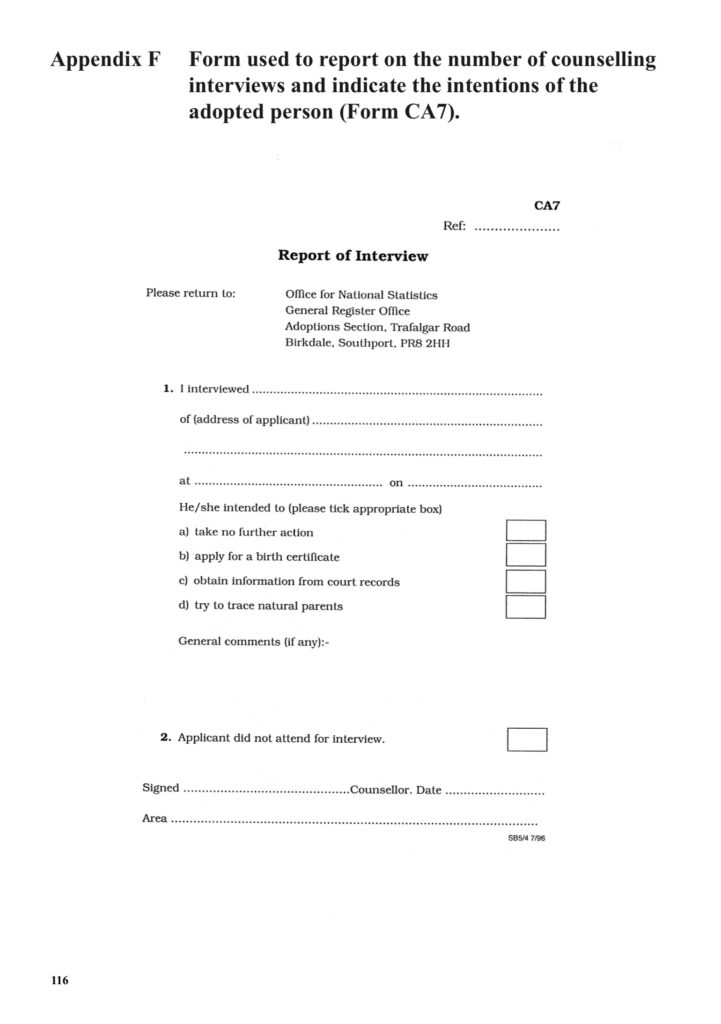

I started by saying that adoptees are almost completely absent from official statistics. When the government does want information about adult adoptees, it gets it. When records were opened by the 1975 Children Act and adoptees in England and Wales were permitted to access our birth records for the first time, statistics were collected about how many adoptees requested our birth certificates, where we had our mandatory ‘counselling’ session (the GRO, social services or our adoption agency), and what we intended to do with the information once we had it (for example, search for our birth family? apply for court records?)7 Ahead of the change in law, a large study was done with Scottish adoptees, who have had access to their birth records since legal adoption was introduced there in 1930, and presented to the Houghton Committee.8 It is so telling that funding was given for a study to gauge the risks (to others) of giving us information about ourselves, and that adult adoptee voices were consulted because they wanted to conduct that risk assessment and not because our voices have any value in themselves.

Even today, the Department for Education dataset is given the nonsensical title ‘Children who are looked after in England including adoptions’ (adoption is now devolved, so only England is included here). Again, there is information about adoptions, but not about adoptees, because we are no longer ‘looked after’ once adopted. This anomaly will only end when true, rational reform comes to the child welfare and family services system and the law on adoption is changed.

——————————————

Official government statistics relating to adoption can be found from these sources:

- Historic adoption tables 1974-2010, archived at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/adoptions-in-england-and-wales/2010/historic-adoption-tables.xls

- The ‘T’ tables in Series FM2 from the Office for National Statistics, available at: (1) Annual report of the Registrar General of births-deaths-marriages in England; The Registrar-General’s Statistical Review, available at LSE Digital Library: https://lse-atom.arkivum.net/uklse-dl1eh01002 (2) archived at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20160108034417/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/marriage–divorce-and-adoption-statistics–england-and-wales–series-fm2-/index.html

- Adoptions in England and Wales, archived at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20160107155716/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/adoptions-in-england-and-wales/index.html

Thank you to Sara Ruth for directing us to some of the above data.

- The resulting study by Julie Selwyn, Dinithi Wijedasa and Sarah Meakings was published in 2014 as Beyond the Adoption Order: challenges, interventions and adoption disruption. Accessed 23/02/2025 at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a74b507e5274a3f93b4825b/Final_Report_-_3rd_April_2014v2.pdf

See also the research brief at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7db954e5274a5eaea65f22/Final_Research_brief_-_3rd_April_2014.pdf (accessed 23/02/2025)

A further article was published in the Children and Youth Services Review in October 2017.

↩︎ - For example: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7d6f2f40f0b64fe6c23b01/Adoption_2013-14_Key_Findings.pdf

↩︎ - A Home for Me? A comparative review of the value of different forms of permanence for children – Adoption, SGOs and Fostering. Accessed 23/02/2025 at https://cvaa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/CVAA-The-value-of-adoption-report-final-Nov-22.pdf. See their press release which refers to it as independent, even though it had a clear brief and agenda.

↩︎ - “The value of adoption to society as a whole has been acknowledged in recent research projects such as that carried out by the Consortium of Voluntary Adoptions Agencies” Recommendations for best practice in respect of adoption, p. 58. Accessed 23/02/2025 via https://www.judiciary.uk/guidance-and-resources/wholesale-reform-to-adoption-process-is-needed-says-public-law-working-group/

↩︎ - Jane Poole, “Exploring Outcomes Relating to Adoption,” Coram, 2023. Accessed 23/02/2025 at https://corambaaf.org.uk/sites/default/files/Marketing/PRD/Adoption/Exploring%20outcomes%20related%20to%20adoption/Exploring%20permanency%20outcomes%20-a%20%20literature%20review.pdf

↩︎ - Margaret A. Keyes, et al, “Risk of Suicide Attempt in Adopted and Non-adopted Offspring,” Pedriatrics 2013 Oct (132, no. 4), 639-646. See https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3784288/.

↩︎ - ONS Marriage, Divorce and Adoption Statistics England and Wales (FM2 no. 27, 1999), pp. 119-121. Archived at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20160111180654/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/marriage–divorce-and-adoption-statistics–england-and-wales–series-fm2-/no–27–1999/index.html

↩︎ - The study was also published as John Triseliotis’ PhD thesis and later as In Search of Origins: The Experiences of Adopted People (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973).

↩︎

6 replies on “Are adult adoptees invisible?”

I found this article very helpful i was interviewed by Leeds Social Services in 1980 ( approximately) since then in spite of repeated attempts to trace my file related to my adoption in 1956 and interview there is no trace of those records, I spoke with Islington Social Services in 2015 and they said that they would search again, however they never found the records. I have no idea of how to get hold of my file, I just have an image of the person who interviewed me in Leeds returning to her desk and dropping the file in the bin then having a tea break.

How does this impact me? I’m left feeling that my life history has no continuity, there’s a void, my rights are of no significance and the relevant authorites have to answer to .

Hi Meah, so sorry you and your information have been treated in this way. If you can bear to, it might be worth asking again, and also asking them to obtain (or help you obtain) your court records at a minimum, even if they can’t find the adoption file.

It wasnt about those that got adopted but about those that did not . They went into foster homes which many were run by charities and the church . This is where the so called elite pedos got their children from . The main reasons why i hate the monarchy and the church , From an adult adoptee who managed to get his adoption records by bypassing the courts and going for Freedom Of Information which trhe courts will NOT tell you about.

As a very rough guide, about 20% of ‘illegitimate’ children ended up adopted by strangers. (Based on figures we have for England and Wales, 1950s/1960s). The rest stayed with their families, were kinship adopted or step-parent adopted, or were fostered/in institutions.

Try contacting Coram they were so helpful in finding my adoption file. I was adopted in Westminster.

Just to add, this is only for those whose case has a connection to Coram https://www.coram.org.uk/what-we-do/our-work-and-impact/birth-records/